Table of Contents

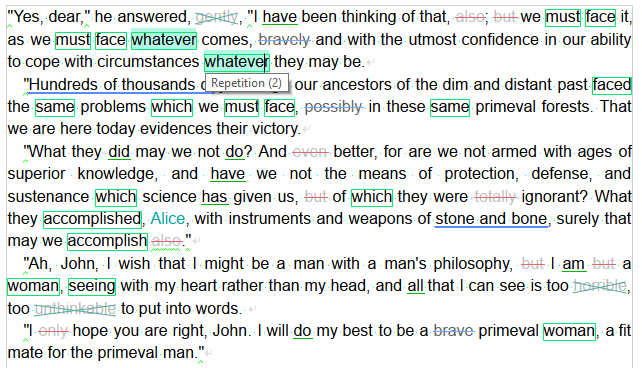

The Papyrus Author Style Analysis forms the core of the in-depth editing features, which you can use to improve your text. It is a guide based on the insights of style lectures, writing classes and professional authors. The Style Analysis is your built-in editor.

![]()

Turn the Style Analysis on and off by left-clicking ![]() on the feather icon in the status bar at the bottom of the window.

on the feather icon in the status bar at the bottom of the window.

The Style Analysis shows filler words, repetitions, “lazy” verbs, sentences that are too long or sticky, weak adjectives, adverbs and more.

Just like a spelling and grammar check, the Style Analysis marks weak spots in your text, but with one important difference:

A spell check marks what is actually incorrect. The Style Analysis, however, makes recommendations where you can take a closer look and improve your text.

Its job is to find spots where your reader might stumble while reading your text. These pull your reader out of the story and disrupt the flow of the text. The Style Analysis helps you find and eliminate these weak spots in your text.

The Style Analysis is not designed to be the final authority, so don’t be alarmed if you turn it on and suddenly your text is filled with colored boxes and circles – that’s normal!

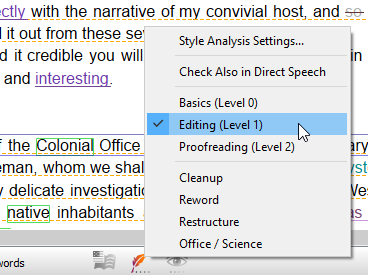

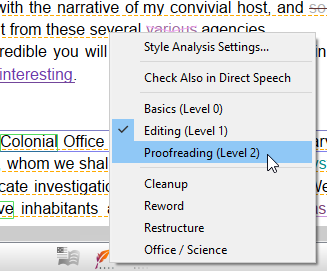

Toggle through Style Analysis sets to focus on different perspectives.

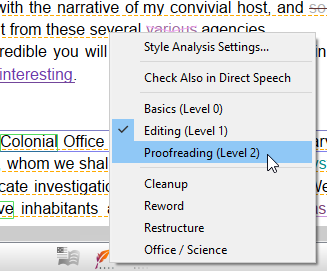

Make use of the various sets in the Style Analysis. There are two types of sets. “Basics,” “Editing” and “Proofreading” are all-purpose sets that highlight over the entire spectrum of the Style Analysis’s abilities. A higher level means higher scrutiny and therefore more marked words.

The other sets are “focus modes,” which put one area of style into the spotlight. “Cleanup,” for example, centers on finding filler words and surplus adjectives, and you can then decide which of these to keep or delete.

You can switch between Style Analysis modes by right-clicking on the feather icon ![]() and then choosing your set from the context menu.

and then choosing your set from the context menu.

![]() In the context menu, you can also open the settings for the Style Analysis. In the settings, you can make changes to our sets or create your own, as well as add or delete words from the filler word list.

In the context menu, you can also open the settings for the Style Analysis. In the settings, you can make changes to our sets or create your own, as well as add or delete words from the filler word list.

Style Analysis Sets

The Style Analysis is designed to be used according to your judgment as the author. When is a “heavy hand” needed and when should the Style Analysis be set on mild, or even turned off completely?

Switching Style Analysis sets

After getting your ideas down on paper, you can go back and improve your style.

For creative writing, you can use the first set “Basics,” which is designed to highlight only a few elements in your text, so as not to disrupt the writing process.

“Editing” is stronger and will mark more text. It will also introduce more categories compared to “Basics”. “Editing” marks judgmental words (when you don’t show, but tell), dull verbs, phrases and more. This is our default mode for the Style Analysis.

“Proofreading” will mark even more in your text. Choose the level of editing that you feel comfortable with and find helpful.

In the final stages of “Proofreading,” you should not strive to get all of the “color” out of your text. That is simply not possible, and frustrating if you try. It’s better to find spots here and there that have been highlighted by the Style Analysis where you can and want to improve your text and focus on those.

The next modes are the “focus modes”. “Cleanup” helps you find terms you could remove from the text: filler words, some adjectives, adverbs and redundancies. “Reword” highlights areas which should be more succinct: over-used, dull and vague words. “Restructure” is about parts that usually need you to change the sentence structure: too long sentences, phrases and nominal style. “Office / Science” is for scientific and daily writing. It helps with all non-fiction writing.

Another thing to consider is what type of text you are analyzing. Two philosophers exchanging thoughts in a pub late at night are allowed to be long-winded. Long, complex sentences fit the part here.

But in a rapid pursuit scene, nobody wants to hear how many adjectives you can use to describe the seats in the car! Your reader simply wants to know – did the villain get away or not?

Thus, if your text is action packed and moves quickly, a stronger setting in the Style Analysis will be your friend. The same applies to most non-fiction. The more difficult or thrilling your material is, the more “cleanly” it should be written.

Take a look at our “Style Analysis Test Document” in the example documents folder to see an example and have a chance to try out the Style Analysis.

What Does the Style Analysis Find?

The Style Analysis points out possible weaknesses in your style by highlighting them with colored markings. When you hover over one of these markings with your mouse, a tooltip will pop up that tells you why this spot has been marked.

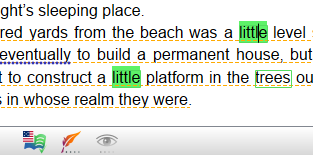

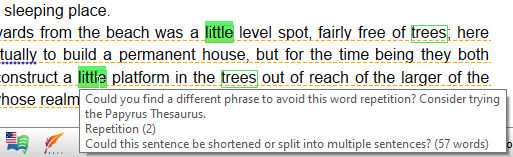

Repetitions of the word “little”

The status bar of your Papyrus Author window shows you a possible reason why the Style Analysis has marked this particular spot in your text.

Items from several categories can be marked as “bad style:”

The first is word repetitions that appear very close to one another. Too many doubled words can make your text sound clumsy.

Doubles in your text will be highlighted with a color (default: boxed green) when you move your text cursor into a word. This helps you find where you repeated the word. If you hover your mouse over a marked word, a tooltip will show how often the word is repeated in its vicinity.

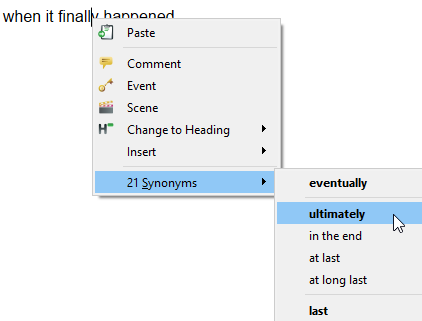

Synonyms in the context menu

The second red flag for the Style Analysis is where a sentence is too long . The longer your sentence, the harder it is for your reader to follow. It takes more energy to read your text, which leaves your reader tired and less likely to want to read more.

Words like “and” and “or” will often point you to a spot in your text where you could turn one long sentence into two shorter ones.

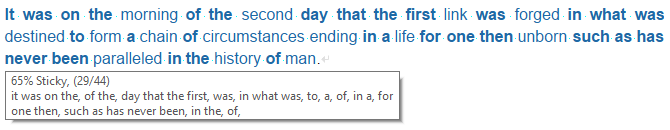

Sticky Sentences contain a high percentage of the most-used words in the English language. These words are naturally low in meaning, and sticky sentences tend to be dull and confusing. Rewrite them to be shorter and more precise.

Finally, there are our word categories. The Style Analysis searches for filler words, vague words, dull verbs and phrases that are often considered “bad style.” Papyrus Author uses a Negative Dictionary that contains all of these words and phrases, organized into categories.

The extent of what Papyrus Author deems “poorly phrased” depends on the Style Analysis set you are using. You can also customize every set or define your own.

Every word in a category (like filler words or adjectives) belongs to a level: 1, 2 or 3. The higher the level, the less certainty there is that the word is necessarily “bad”. Thus, words in category 1 are very often bad style. Using words in category 3 can be argued and whether their use is appropriate will depend more on context. Category 2 is in-between.

Our default Style Analysis set “Editing” has all word categories turned on, but limited to level 1. Therefore, you will get the most important style hints of all areas combined when using it.

The word categories you can find in the Style Analysis are:

| Filler Words | Filler words seldom say anything. They are often part of speech, but should rarely appear in text. |

| Adjectives or Adverbs | Too many adjectives and adverbs often show an over-described, cumbersome text. Many common adjectives can be improved by a more fitting one. |

| Vague Words | Vague words state something but describe very little. |

| Dull Verbs etc. | Dull verbs or lazy writing is often a lackluster phrasing that is not on point. |

| Phrases | Phrases and clichés might annoy readers and should, if at all, only be used in direct speech. |

| Time Sequence | Describing events not in an order but simultaneously is rarely necessary. “While A happened, B happened as well” is often regarded poor style in writing schools. Time Sequence also includes “show, don’t tell”-breaking words like “suddenly”. |

| Judgmental |

Depending on the point of view of the story, judgment might be a style weakness or even a narrative mistake. If you do not use first-person narration or an omniscient third-person narrator, the narrator should not “know” the thoughts of characters in the story. Judgmental also includes words that break “show, don’t tell” by stating instead of describing. “He thought she was beautiful.” |

| Redundancies | Redundancies state the same thing twice and can often be reduced to part of the phrase. The special emphasis of a redundancy is often unwanted. |

| Nominal Style | Nominal writing depends on verbs created from nouns and nouns created from verbs. It is aloof and less definite than active style, often used in bureaucracy and business writing. |

| Negative Constructions | Unless it is intended as a method of narration, telling what is instead of what is not paints a more vivid picture. |

| Miscellaneous | Terms that fit in no other category, and those that you added as custom words. |

You can also add entries to the list of filler words that you would like pointed out in your writing. Words already in the list can also be edited.

Style Analysis Settings

Toggle through Style Analysis sets to focus on different perspectives.

The style analysis setting can be accessed by right clicking the feather icon ![]() located in the status bar at the bottom of your text window and choosing “Style Analysis Settings” or in Papyrus Author “Preferences” → “Spell Checking” → “Style Analysis.”

located in the status bar at the bottom of your text window and choosing “Style Analysis Settings” or in Papyrus Author “Preferences” → “Spell Checking” → “Style Analysis.”

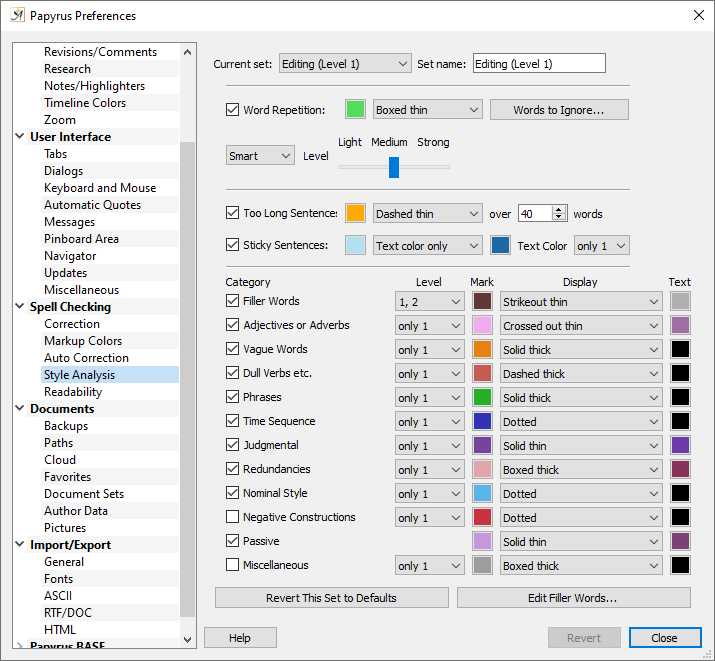

In the Style Analysis settings dialog, there are ten slots for different “style sets” for you to choose from.

The first have been preset, but you are free to modify them or give them a different name.

The unnamed slots are placeholders for you to create your own style sets.

“Revert this set to defaults” will revert all settings in the current set back to the presets that come with Papyrus Author, so you are safe to try out different changes.

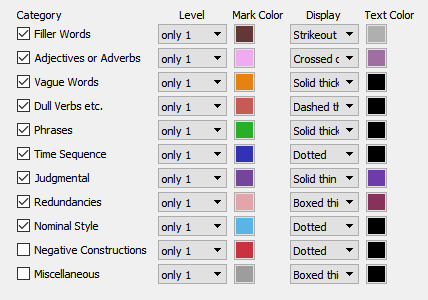

Style Analysis settings

You can change settings for the various style categories in this dialog, including how a certain category will be displayed in your text (zigzag lines, color, etc.).

The Style Analysis will be applied to those areas of your text–main text, notes, tables, etc.–that have been selected for spellchecking under “Other Options” in the “Correction” dialog.

For every style set, you can decide whether you would like to check “No style and grammar check in direct speech.” The Style Analysis will then ignore direct speech. This comes especially in handy when you want to examine the narrative around your dialog and not be distracted. Spoken language is different to narrative in that filler words, vagueties and phrases are often intentional.

There are many types of issues that Papyrus Author’s Style Analysis can find:

- Word Repetitions

- Too Long Sentences

- Sticky Sentences

- Negative Lexicon (Several Categories: Filler Words, Adjectives, Dull Verbs, Phrases, Etc.)

Word Repetitions

Using the same word repeatedly within a few lines of text is something to avoid if possible, as your reader will be distracted by the repetition.

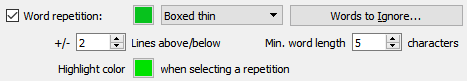

Word repetition settings

If you have the “word repetition” option turned on, Papyrus Author will search for “doubles” within the number of lines you have specified and highlight these for you. Most style sets come with a default value, so you can work with the Style Analysis without configuring anything.

You have the option to set how many lines above and below a word should be searched for repetitive words (we recommend starting with 2 and not setting more than 8).

You can also set a character minimum for the words to be marked as a repetition. Words that have three letters or fewer tend to be articles (a, the), prepositions (for, on, at), auxiliary verbs (has), etc, which are often not problematic if used repetitively.

Papyrus Author’s Style Analysis contains a “List of Words to Ignore” with words that will not be marked if repeated, even if they are over the character limit. You can edit this list as you choose. This list contains the most important commonly used words (the, a, an, is, …).

Papyrus Author will also consider inflected forms in its search for word repetition, e.g. not only “I write” but also “he writes,” past tenses and participles “wrote” and “written,” as well as plural forms, not only “book” but also “books.” The aim is to find everything that a reader would experience as a repetition.

The algorithm for stemming and inflected forms depends on the language settings within Papyrus Author (e.g. “Language and Hyphenation” under the menu “Text”). The default is set to English.

When you place your text cursor in a word that the Style Analysis detected as a repetition, the word doubles in the surrounding area will be highlighted. Just click into a word.

When you place your text cursor in a word that the Style Analysis detected as a repetition, the word doubles in the surrounding area will be highlighted. Just click into a word.

The highlighter color can be changed in the Style Analysis dialog.

Highlighting will disappear as soon as you begin working on the text. It’s possible that words will be highlighted that are not marked themselves. These belong to the word stem, but are shorter than the set minimum word length.

Too-Long Sentences

Sentences that drag on and on are another mark of bad style. When your reader has forgotten how the sentence started by the time he or she reaches the end, your sentence is too long.

Too long sentences settings

The Style Analysis can highlight those sentences which exceed a limit of words. The number is defined in the style set. With the “Editing” style set, for example, a sentence counts as too long exceeding 40 words.

A “sentence” is specified here as one that ends with a page break, line break, or paragraph break, a colon, or a period, exclamation mark or question mark. Usually “anything “between two periods” is a sentence.

Sticky Sentences

Sticky sentences say something with many words, when often it could be said with less. Did you notice this first sentence was a little sticky? They contain a majority of the most-used words in the English language. Naturally, these words are easy to use and low in meaning. This results in sentences that can be boring or hard to follow, even if they contain great content.

A sticky sentence with its glue words in bold.

When you hover your mouse over a sticky sentence, the tooltip will show how sticky your sentence is and which parts of the sentence are considered “glue”. See if you can remove or exchange glue words while keeping the original meaning. Your sentences will often be sharper afterwards.

Sticky sentences settings

Showing sticky sentences can be turned on or off in the Style Analysis settings dialog. You can also change the text color and set up additional markup. By default, sticky sentences have their text color set to blue and no additional markup like underlining.

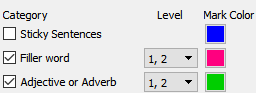

In the popup box on the right, you can set the sticky sentence sensitivity. Similar to the style word categories, “only 1” is the default setting. “1, 2” will find even more sticky sentences.

Negative Lexicon for Filler Words, Weak Phrases, Etc.

There are many well-known style conventions and there are typical style mistakes that many writers find sneaking into their texts despite their best intentions.

Your text will flow better and draw your reader in more effectively without these negative tendencies.

Enter a word into the search bar to find it in the list. To remove a word, select it and click on “Delete.” To add a word, click on “Add.” You can also define the category and level of your entries.

Words can belong to several categories at the same time, “important” categories take precedence over lower ones. Some categories overlap a little, so you don’t lose out on important words which could be tagged either way.

If you enter a word into the “miscellaneous” category, it will take precedence over other entries.

The level of a word will determine if a style set marks it. You can assign your words a level from 1 to 3.

Levels in the Style Analysis settings

If a filler word has been assigned level 2, but the dialog level is set to “only 1,” the word will not be highlighted. Only when the level in the dialog is set to “1, 2” will the word be marked in your text. This way you can create a threshold for how important you rank an entry.

To assign a level for a particular word in the list simply choose a level from the drop-down menu in the “Style Analysis Settings…” dialog (either [1], [2] or [3]). If you do not assign a level, it will automatically be set to [1].

The Style Analysis is not case sensitive so listed filler words will be found in your text whether they appear in lowercase or with capitalization (e.g. at the beginning of a sentence).

Style Categories

There are various categories of words which can detract from your text in different ways. Thus, Papyrus Author has predefined categories to organize the specific types of stumbling blocks that could appear in your writing.

Style Categories

Categories can be assigned different colors and markup or underline styles.

The “Style Categories” are:

- Adjectives or Adverbs

- Vague Words

- Dull Verbs

- Phrases

- Time Sequence

- Judgmental

- Redundancies

- Nominal Style

- Negative Constructions

- Miscellaneous

Filler Words

This category contains words that take up space in your sentence and make it unnecessarily inflated. Filler words can very often be removed from a sentence without even needing to change the sentence structure afterwards.

When writing a rough draft, we often load it with filler words, either because we need time to formulate our thoughts, or because we write too much like we speak.

Compare these two sentences:

Basically, he just wanted to tell her that he loved her.

He wanted to tell her he loved her.

Notice the difference? The sentence style changed drastically by removing the filler words basically, just and that. The meaning of the sentence stayed the same. Sometimes, you might want to keep a filler word for emphasis or context. For example, the just in the sentence above could be important in context. Most of the time though, filler words bloat your sentences and provide no additional meaning. Filler words work best when they are used rarely.

The category can also be expanded by words that you personally tend to use too much. If you find them constantly slipping into your text, you can add them to the filler word list and Papyrus Author will point them out for you. Any words that have not been assigned a category will fall into this category automatically. Words with custom categories are tracked as miscellaneous.

As always, you can add your own words to a set or delete words by clicking on the ![]() button.

button.

Adjective / Adverb

Of course, you shouldn’t do away with adjectives and adverbs completely, but it is a good idea to be aware of how often you use them. Less is often more.

“A heavy iron bar” is an example of over-explaining. Anyone who has ever lifted anything made of iron knows it is heavy. Eliminating the adjective does not cost you any information.

It can get even worse for adverbs. In “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft,” Stephen King claims “the road to hell is paved with adverbs.” Whenever you use an adverb, ask yourself if you really need it to get the point across. Will the reader not understand the way somebody speaks, moves and acts from using the right verbs and context?

Look at this sentence: “Put the knife down!” she shouted fearfully.

Do we need to be made aware she shouted “fearfully?” We will probably understand anyway.

The combinations “adjective + noun” or “adverb + general verb” can often be replaced by a single specific word that also fits the situation.

For example, instead of “walking slowly” along the beach, your character could “stroll.”

You can add or delete words in this category, as well as assign them a level, by clicking on the ![]() button. This category will contain all words followed by (Lazy Word), (Weak Word), (Adjective) or (Adverb) in the list.

button. This category will contain all words followed by (Lazy Word), (Weak Word), (Adjective) or (Adverb) in the list.

Vague Words

Vague words are a list of nouns that try to state something, but describe very little. They are broad in nature and limited in helping your reader imagine your story.

Compare the following sentences:

She watched the man drop his things into the crate.

Who is the “man?” Do we know him? What “things?” Is she talking about pants, weapons, apples, sporting equipment?

She watched the stranger drop a bundle of keys into the crate.

Maybe the keys are important for the story, maybe they are not. The man could just as easily drop “something small” into the crate. Try to describe like the actual observer would, and you will often come up with better fitting terms.

Dull Verbs

Using verbs that don’t appropriately describe the action being performed can also be considered bad style.

When your characters “went” somewhere, “did” something, “liked” it and “felt” good about it, their actions will be perceived as very bland.

Compare the following two sentences:

We went to get flour and afterwards made cake. Mom liked it a lot.

We bought flour and afterwards baked a cake. Mom was delighted.

This can be a useful aid to vary the verbs you are using in your text, but if you find it more bothersome than helpful, feel free to turn it off by deselecting the checkbox.

Phrases

Phrases are word constructions that over-complicate, unnecessarily fill or dull a statement. Our “Phrases” category consists of three sub-categories: complicated phrases, empty phrases and weak phrases.

Complicated phrases are often used when the author wishes to make a special point of something. This is seldom necessary and you can transport your message in an easier way. For example instead of writing “in spite of the fact that,” try using “although.”

Empty phrases beat around the bush or don’t actually say anything.

Compare “It was essential that we got there.” vs “We had to get there.”

Weak phrases can be rewritten for style improvement.

Compare “It was possible to detect the submarine.” vs “They could detect the submarine.”

Phrases can also be added to the filler word list, with or without punctuation.

Time Sequence

Describing events simultaneously is rarely necessary and takes emphasis from the actual story. Try telling in succession. A person’s focus is usually on one thing at a time. When you tell that things are happening simultaneously, you are trying to avoid a problem which cannot easily be solved by inserting the word “while.” Is simultaneousness really necessary for the story? Will the imagination of the reader change when you describe the events one after the other?

Check the following sentences:

While John was looking at her, she explained the situation.

John looked at her. She explained the situation.

John will probably not start looking somewhere else as he is being talked to.

“Time Sequence” also includes “show, don’t tell”-breaking words like “suddenly” and “immediately”. Do you need those to announce your action? “Suddenly” will catch the reader’s attention–and reduce the impact of the following statement.

Judgmental

This category is for words and expressions that would cause any editor or creative writing professor to exclaim “Show, don’t tell!” The Judgmental category entries are split between (regular) “Judgmental” and its sub-category “Clairvoyance.”

“Judgmental” depends on the narrative point of view.

If I am writing in the first person, from my point of view, I know exactly how I am feeling and can easily write about it. It is possible to write a book that takes the reader by the hand and gives him or her a glimpse into what is going on in the minds of the characters.

As a neutral narrator, however, I don’t know–I am not allowed to know–how the person across the table is feeling or what they are thinking. I can only make reasonable assumptions based on their actions.

Readers pick up on logical mistakes easily, such as writing about thoughts and feelings that the narrator could not possibly know about. These mistakes quickly become tiresome.

Any type of clairvoyance is a narrative mistake when writing from the “third-person objective” point of view. All kinds of feel/think/know-words are marked as “clairvoyance.”

The same goes for passing judgment on characters, events or items. A factual narrator can’t state that “Edward was evil,” or “Edward is beautiful.” Only indicate to the reader that Edward is evil based on his actions, and that he is beautiful by how the ladies swoon.

Thus, there is a category for judgmental terms (“beautiful,” “bad,” etc.) Such words tend to make the reader ask themselves, “OK, but why exactly? How do I know this is true?”

Redundancies

Redundancies state the same thing several times in a row. When you deliberately use them, you put a special emphasis on a fact. It gets a lot of attention. But repetition is dangerous, if you use it regularly, it will bore the reader.

Most of the time, you will want to reduce a redundancy to one of its parts–and not lose any meaning.

Compare the following sentences:

Outside in the yard knelt down a creature made entirely of frozen ice.

In the yard knelt a creature made entirely of ice.

“Outside” might make us learn that we are actually inside. But in a story, would we not know this from the narration, as we observe this scene from a window? “Kneel down” and “frozen ice” are clear redundancies. If it was “frozen yoghurt,” it might be different.

Nominal Style

Nominal style uses nouns instead of verbs and the passive voice instead of the active, which makes your text more difficult to read and understand.

This category also includes words often found in official letters or bureaucratic forms. These are in the sub-category “Legal Language.” It goes without saying that such words make your text cumbersome.

Checking for nominal style makes sense even beyond writing prose. If you write manuals or work in governmental or law offices and write letters to “normal people,” it is essential that the addressees are able to understand the letter they have received.

If you use nominal style to tell a story, your reader will feel they might as well study the phone-book.

Compare the following sentences:

I will make a decision when I have knowledge about the newest events.

I will decide when I know about the newest events.

It is your decision, but unless your character speaks like this on purpose (“absent-minded professor”), the second sentence will read less cumbersome. Many nominalizations can also be replaced with a different verb. You could write “learn” for the prospect of “having knowledge.”

I will decide when I learn about the newest events.

Just like the other categories, you can assign additional words to the “Nominal Style” category.

Negative Constructions

Every time you tell what is not instead of what is, you are using negative constructions. Telling “what is” will generally paint a more vivid picture compared to “what is not.” Try imagining something that is not. Of course, there are times when it can be fitting to tell what is not, especially, when it contrasts common expectation. Unless it is a special form of narration, negative constructions slipped through and should be rephrased.

Compare the following:

I had not expected Tom to call.

I was surprised when Tom called.

As always, it’s your call.

Miscellaneous

The “miscellaneous” category can be used for your own words that don’t seem to belong to any other category. Simply write the type of word behind the word in parentheses and add it to this category. You can define any type of your choosing, like “doubleplusgood (newspeak).”